2020, the year of the pandemic, brought with it new popular words and phrases. “New normal”, “social distancing” and “flatten the curve” stand out, but also “travel bubble”.

These new pop phrases have something interesting in common: they combine two semantic opposites in one phrase. “New” is about something we don’t know yet, the opposite of “normal”, something we know and are used to. “Social” is about getting together, the opposite of “distancing”. A curve is curved, the opposite of straight and “flat”. And “travel” is about free movement, while the inside of a “bubble” is a confined space. This results in a semantic reversal where normal is not normal, social is not social, and travel is not free movement. Language reflects its time, and so do artifacts.

A bubble can be a concept, but also an artifact. As part of “The Elements in Design”, I looked into the history of bubbles in art, design and science. In the nineteen-sixties, bubbles weren’t seen as symbol of confinement. Instead, they promised escape, lightness and ephemerality, flexibility instead of rigidity, and spontaneousness instead of fixed rules.

A Short History of Bubbles

Francesco del Monte, born in Venice into the noble Tuscan family Bourbon del Monte, was a remarkable personality: amateur alchemist, cardinal of the Roman Catholic church, glass collector and unofficial intermediator for the affairs of the Medici in Rome.

He was a great patron of the arts and sciences, and among the many talents he supported were two very remarkable ones: Galileo Galilei and Caravaggio. Francesco del Monte had a beautiful garden villa at Porta Pinciana in Rome, and there he had a small, vaulted alchemy workshop for which, sometimes between 1597 and 1600, he commissioned young Caravaggio to paint a ceiling mural.

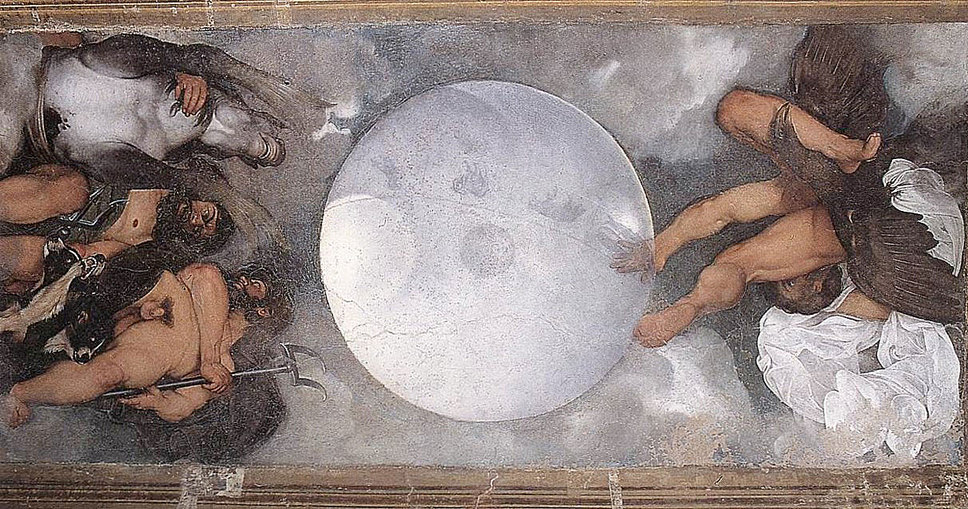

Caravaggio, extravagant and highly gifted, depicted the gods Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto in an extreme foreshortened perspective, and he placed a translucent bubble in the center: a celestial sphere in which the sun, representing fire, revolves around the earth. In the symbolism of the alchemists, Jupiter stood for air, Neptune for water, and Pluto for earth.

Not only the perspective, also the depiction of the bubble’s intricate light refractions has not been seen before – Caravaggio must have consulted the scientists in del Monte’s salon, Galileo Galilei and possibly Giovanni Battista della Porta, to achieve his stunning result.

The Cardinal’s garden villa, later called Casino Aurora, became a fixture on the Grand Tour in the 18th century and was visited by personalities such as Goethe, Stendhal, Gogol and Henry James.

However, they did not see Caravaggio’s mural: it was painted over and rediscovered only in 1969. Francesco del Monte’s other famous beneficiary, Galileo Galilei, went on to discover that air is not, as it was assumed until then, weightless, but has a weight (he defined it as 1/660 the weight of water). To come to this conclusion, he used a bubble filled with air, made from a pig’s bladder. He also found that Copernicus was right and the earth revolves around the sun – to the dismay of the church and at the cost of his freedom and career.

Del Monte had a gift for picking extraordinary talent, but he could not protect Galileo, his greatest protégé, from his powerful contemporaries’ self-centered worldview. For them, it was themselves who are sitting in the very center of the universe. The Inquisition forced him to recant, and he was placed under house arrest for the rest of his life.

Caravaggio’s depiction was the result of his talks with Galileo when they met in villa Aurora. The celestial bubble, the focal point of Caravaggio’s mural, represented the universe. Today, over 400 years later, this idea of a scientist and an artist is stronger than ever. Physicists today think of the universe as a bubble; it just contains a lot more more than one earth and one sun – where it is observable, the universe holds 400 billion billion suns and many more planets.

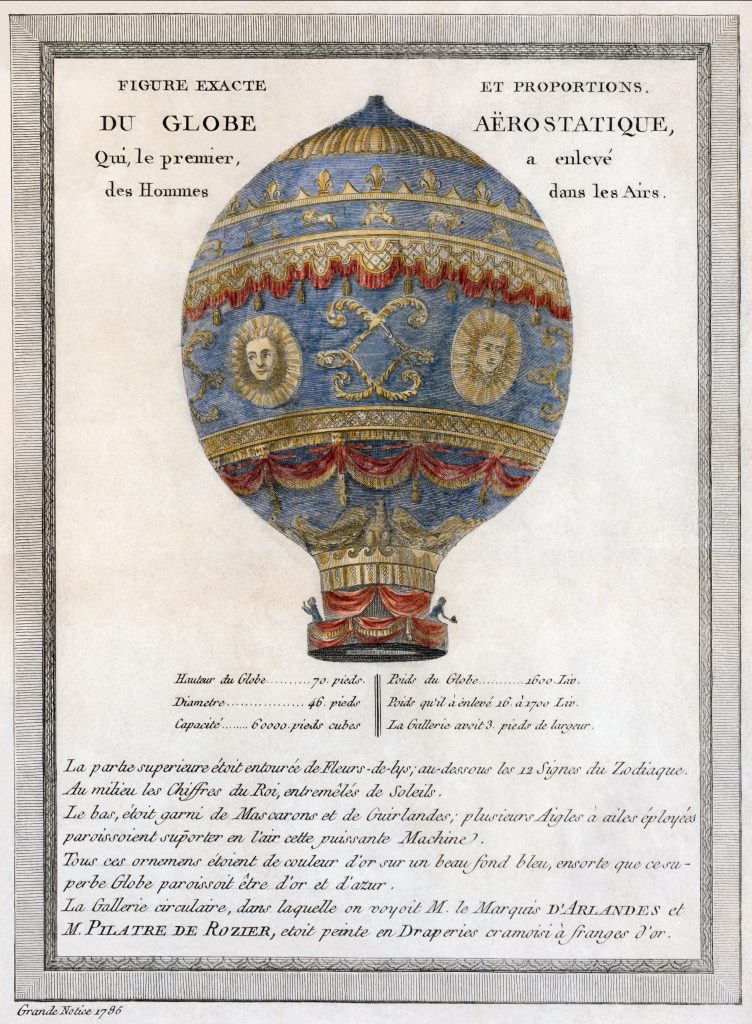

In 1720, Bartholomew Gusmao allegedly built a flying machine propelled by hot air and flew it himself in Lisbon in front of the Portuguese royals. In 1783, the brothers Montgolfier constructed a balloon made from sackcloth and paper, held together by cord. They attached a basket with a sheep, a duck and a rooster and demonstrated its flight to King Louis XIV and Marie Antoinette at Versailles palace. The bubble was flying now.

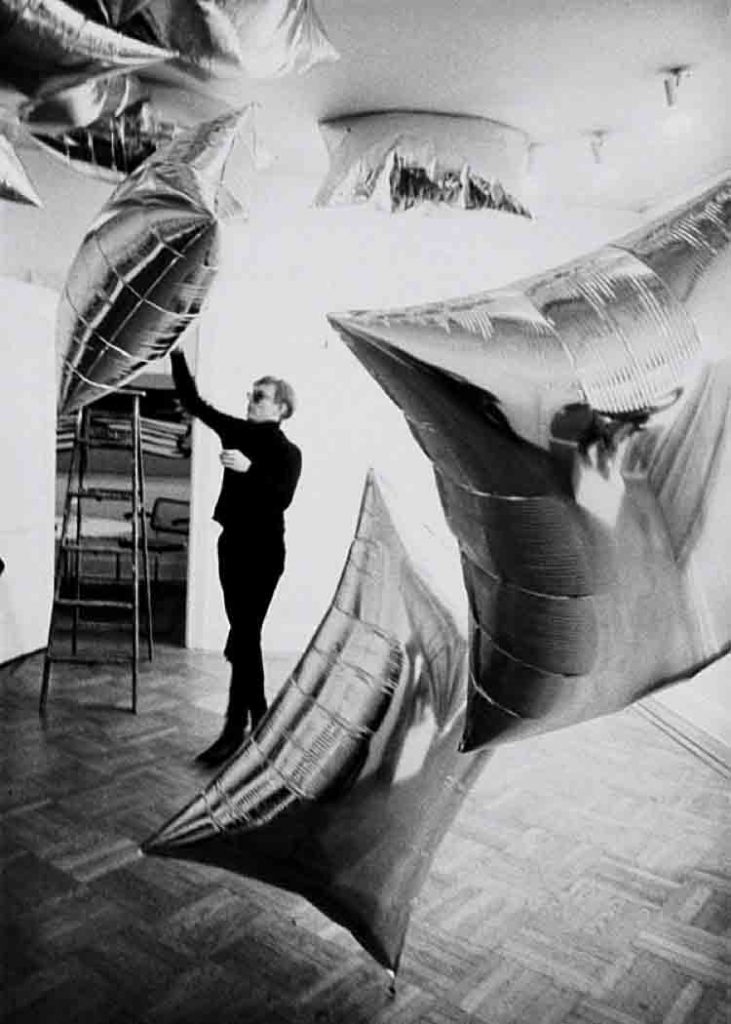

It was again in the sixties of the twentieth century that capturing air became fashionable. In tune with the free-spirited theme of the times, bubbles inspired designers of a whole generation. In 1966, Andy Warhol showed his ‘Silver Clouds’ – helium-filled mylar cushions – at Leo Castelli’s gallery in New York.

In 1967, Italian furniture maker Zanotta introduced ‘Blow’, the first mass-produced inflatable chair for indoor use, designed by Jonathan De Pas, Donato D’Urbino, Paolo Lomazzi and Carla Scolari.

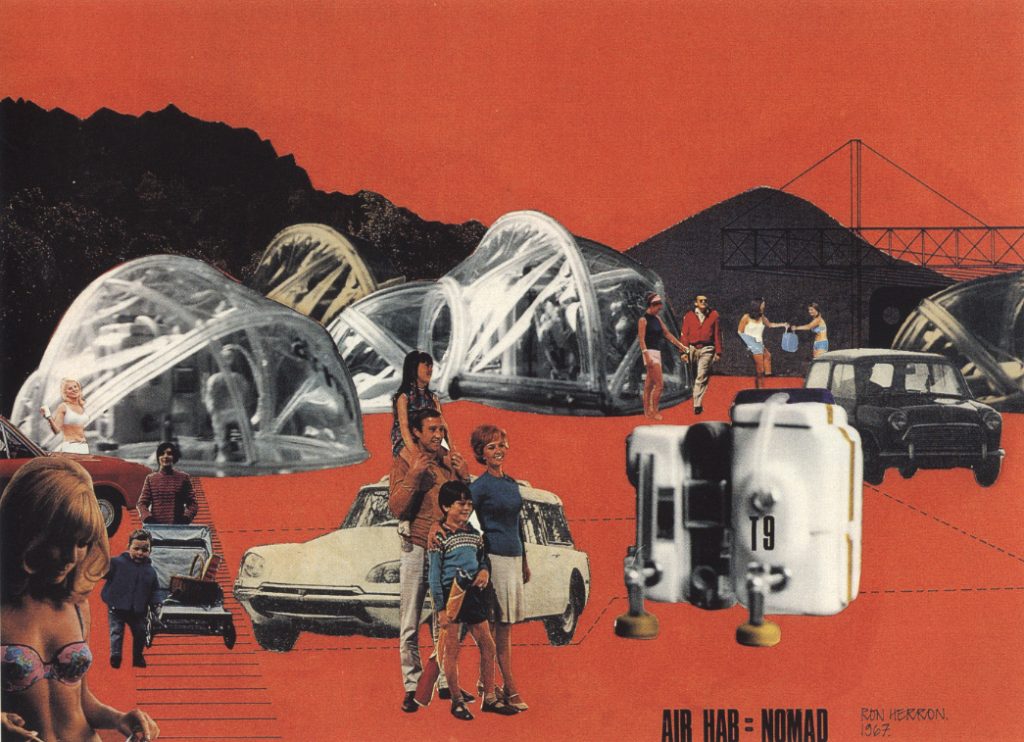

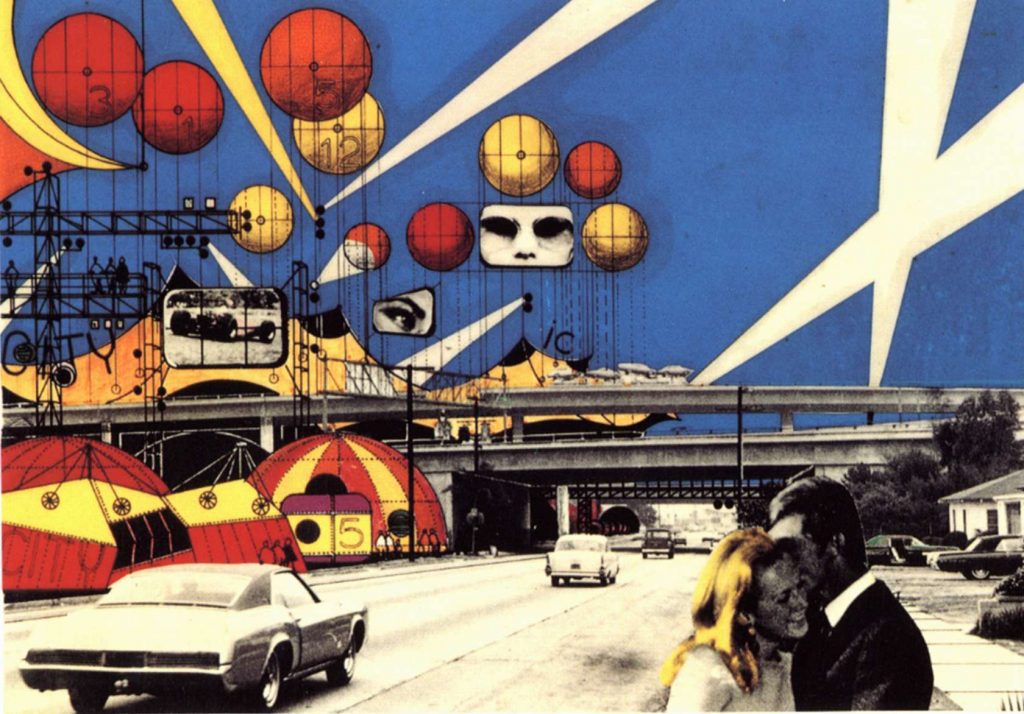

British architecture group Archigram proposed projects such as ‘Air Hab’ and ‘Inflatable Suit House’. In one of Archigram’s publications, Archigram 4, Warren Chalk writes about inspirations from “space comics, mobile computer brains and flexing tentacles”.

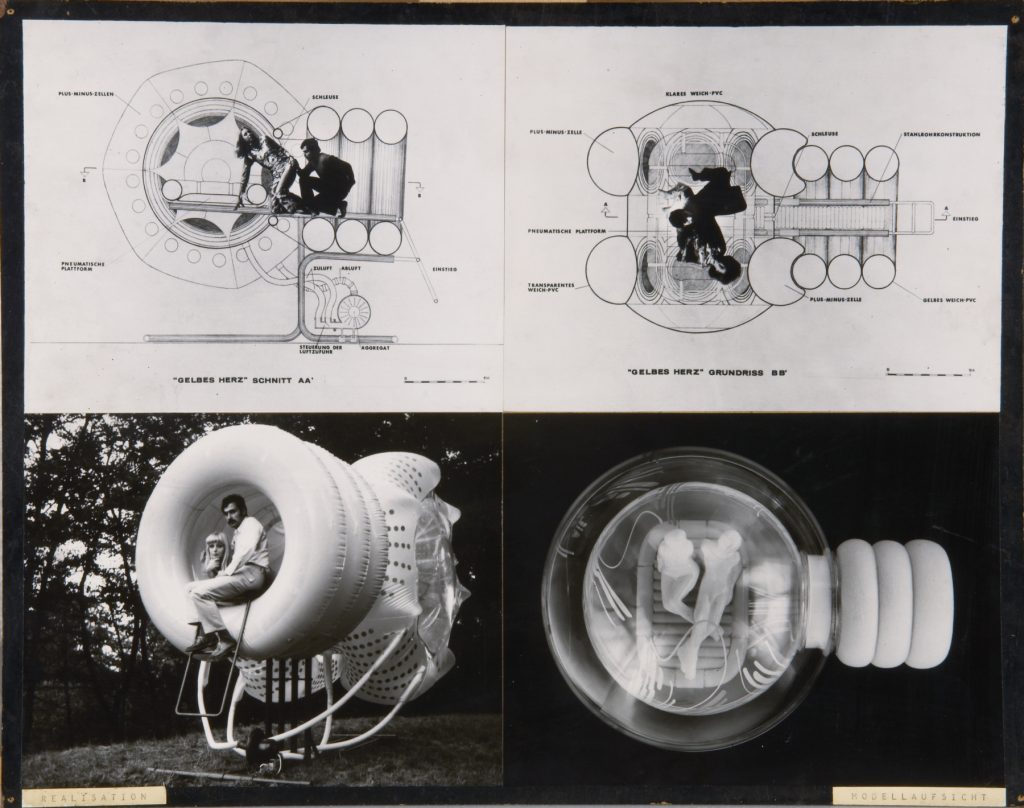

Austria’s Haus-Rucker Co. presented ‘Yellow Heart’, an air-filled PVC structure on a steel frame which inflated and deflated to suggest a heartbeat.

The world exhibition 70 in Osaka featured a variety of inflated exhibition halls. The US Pavillion was the largest free-span inflatable dome of its time.

Balloons also found their way into television series: In ‘The Prisoner’, an iconic British Science Fiction series filmed between 1967 and 1968, the main protagonist finds himself captured in ‘The Village’. When he attempts to escape, he is followed and captured by an large white balloon called Rover, an autonomous, intelligent object.

Inflatables symbolized the spirit of the times, carrying with them the idea of generation 68. Balloon designs promised escape, lightness and ephemerality. They offered flexibility instead of rigidity and spontaneousness instead of fixed rules.

In the late sixties and early seventies, balloon structures seemed to be the future of architecture. It was a future which did not happen. Except in some sports halls, ballon architecture did not take on; for everyday tear and wear, balloon structures proved to be too vulnerable.

Designers, artists and engineers are still fascinated by bubbles. The eMotion spheres by German firm Festo combine science fiction ideas of the sixties with technology from the 2010s. Designed to show the possibilities of autonomous guidance and monitoring systems, these autonomous flying balloons are equipped with eight small adaptive propellers and infrared LEDs. The balloons, controlled by a central computer, move out of the way of other flying objects, adapt to varying atmospherical conditions to maintain their formation, and charge themselves independently.